Deborah Painter (USA)

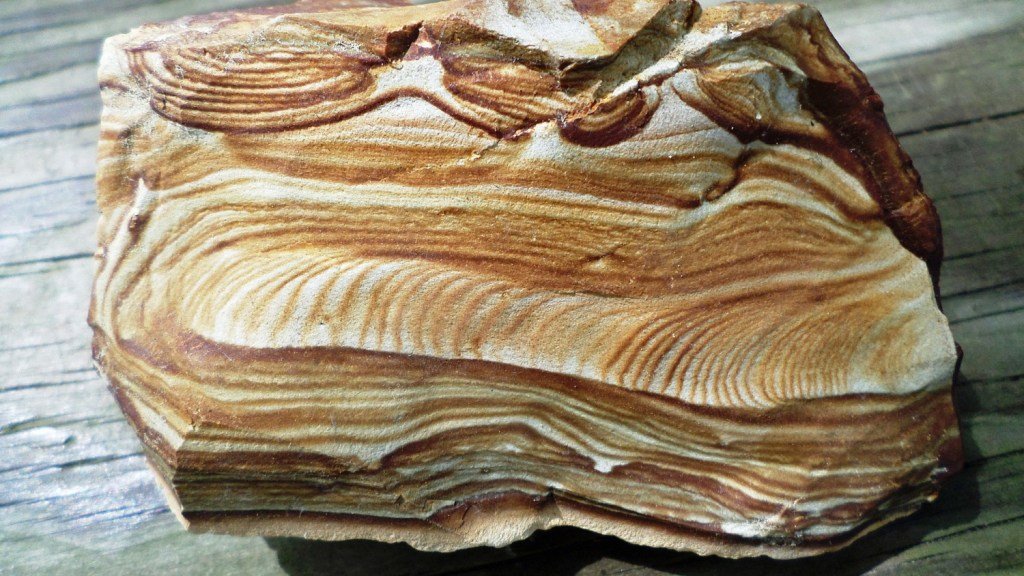

Earlier within the month of September 2022, my pal David and I spent a day with a fellow named Ellery, a long-time member of a rock amassing membership we joined a 12 months in the past. Ellery allowed me to {photograph} a few of his rock and mineral specimens, including a rough piece of ‘wonderstone’ of approximately 30cm in length and 19cm in width, from southern Utah, USA (Fig. 1).

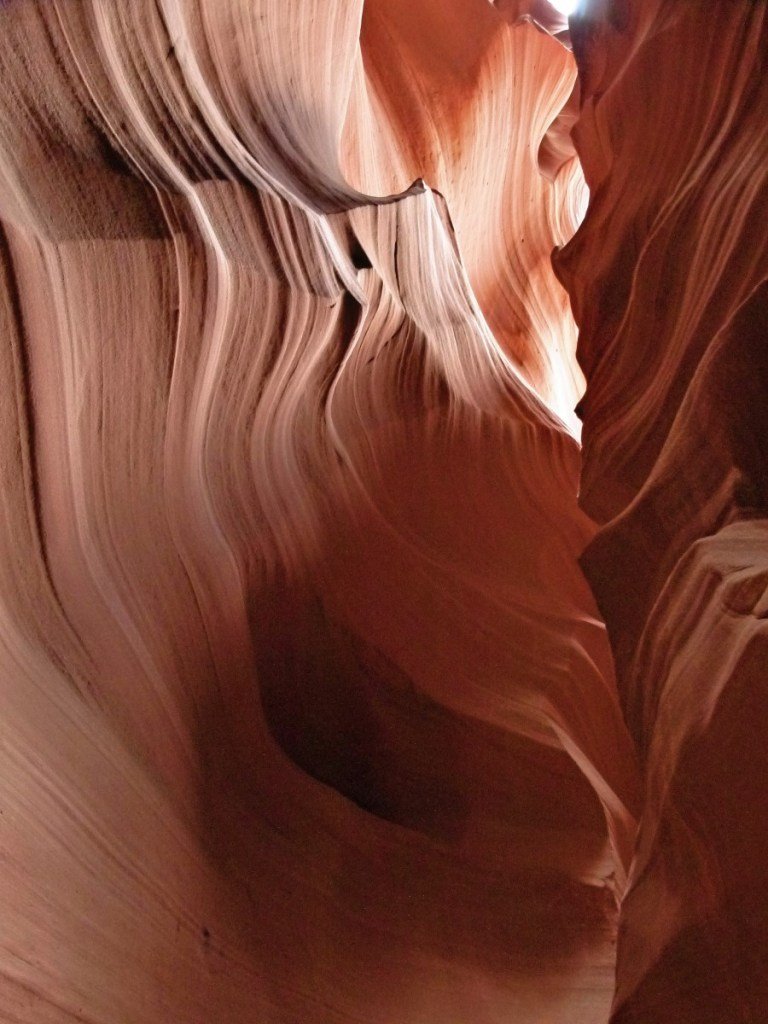

The piece contained what looked like a painting of the flanks of a slot canyon one might see in the very area where it is found (Fig. 2).

On the opposite side of the same specimen was a fish’s head, complete with an ‘eye’ (Fig. 3).

None of the images were artificial or cut in a particular way to bring out these ‘images’. I was instantly reminded of the pietra paesina stones of the Florence area of Italy. The latter have been collected and polished since the 1500s in Europe; and they seem to depict cityscapes, cliffs, seashores and harbours filled with ships. It’s all an illusion, but an awe-inspiring one.

Wonderstone is a silicate mineral of the chalcedony group and pietra paesina is limestone, but both have iron oxide in common as a means of forming the amazing ‘scenes’ revealed. In pietra paesina’s case, manganese is also part of the chemical makeup creating the ‘artwork’.

There are two rock varieties in the western United States that are commonly called ‘wonderstone’. One is an igneous rock – a tuff that occurs in Nevada. The chalcedony wonderstone is known as Shinarump Wonderstone, from the Shinarump member of the extensive upper Triassic Chinle formation of Utah, Nevada, Colorado and several other states. The sandstone making up this formation was a large depositional area known for lake and wetland environments. At the time (approximately 225 million years BCE), the conglomerates of the Shinarump member were formed, the land-dwelling life consisted of arthropods, land snails, fish, amphibians, egg-laying mammals, early dinosaurs, turtles, conifers, and ferns and their allies. The seas were filled with cephalopods, gastropods, corals and modern looking fish.

Iron was present in an aqueous solution within the sediment of braided streams in the area of the future Shinarump member. It formed the reddish cement and the stain. At the present day, iron is present in many streambeds and is not unusual at all. Therefore, what unusual circumstances caused the wonderstone to have a cement that made the striking colour and patterns?

The origin of these iron mineral patterns or bands, known among chemists as Liesegang rings (Fig. 4), is not completely understood.

Oxidised iron minerals, pyrite and siderite, are known among geologists as Iron II. Oxidized iron minerals, hematite and goethite, are known by geologists as Iron III. If one electron is added to common iron containing minerals found in wet sand, the result is reduced iron that can be transported easily in water. However, siderite and pyrite usually form in this process, and they do not have Liesegang rings. Neither are they red in colour. Something else has to happen. There are two possible explanations:

- One explanation is the following. When oxygen rich groundwater saturates the sediment, the pyrite dissolves and turns into an acidic solution rich in iron. The Iron III goes to the source of oxygen and, if circumstances occur that cause the sediment’s chemical composition to neutralise, the iron then precipitates to form the red (stain) and the Liesegang rings (cement). The sediment later becomes sandstone and chalcedony.

- Another explanation, advanced by Richard M Kettler and David B Loope in their paper on the origin of Shinarump Wonderstone, is that the mineral siderite had already formed in the sediment prior to its becoming rock. The sediment hardened and cemented into sandstone and chalcedony before the Liesegang rings formed. The Colorado Plateau was uplifted over the course of millions of years and, while this was happening, more groundwater rich in oxygen penetrated the Shinarump sandstone. Bacteria that oxidise iron to make energy for themselves transfer an electron from less iron rich minerals to oxygen and thus create the more iron rich minerals goethite and hematite. Bacteria continued to oxidise the aqueous Iron II and turn it into Iron III. Iron III oxide then precipitated to create the Liesegang rings. The iron oxide staining was created because inter-diffusion of oxygen and iron took place, post-cementation.

Shinarump wonderstone occurs as blocks, but also occurs as small, cobble-sized pieces. Only some require any sawing or slicing to reveal the beautiful patterns. According to the Kettler and Loope paper referenced above, there is a private quarry on a large piece of property designated as MidnightPropWashington 2 administered by the Utah Department of Natural Resources. Visitors are required to obtain a walk-in access authorisation number and present it if someone asks. The authorization number is free of charge and available at http://wildlife.utah.gov/ walkinaccess/authorization.php.

Anyone collecting should adhere to the regulations listed in the Utah Department of Natural Resources. The quarry is located 14.5km northwest of Hildale, in southernmost Utah. Begin at the intersection of Little Creek Mesa Road with State Highway 59. The sign marking the intersection reads 400N and State Street. Drive west on 400N for 0.4km. The road will bear south. Drive south on 7400E for 0.80km to Little Creek Mesa Road and turn to the southwest. After 1.4km on Little Creek Mesa Road, take the left fork in the roadway and leave Little Creek Mesa Road. Proceed 0.4km to the southwest and park.

No quarries exist for Italy’s pietra paesina. One must simply have an eye for small blocks of limestone found in the Florence area (Fig. 5) that have the right exterior colours that suggest there may be pietra paesina ‘compositions’ within.

Then, the stone must be sawed in just the right way along the right plane to see the pietra paesina. Needless to say, it is a procedure filled with anxiety on the part of the preparer, because, if it is not sawed along the right plane, the marvellous pictures will not be visible (Fig. 6).

And what marvels they are. A human artist could not do better to create such impressionist art. The arch at Cabo San Lucas, Playa del Amor in Mexico is amazingly duplicated by a particular specimen visible on the Pietra Stone website listed in the References list at the end of this article. Another seaside feature, Contessa Beach at Elba Island in Italy can be seen in a specimen on the website. Monument Valley in Arizona, USA is uncannily reproduced in a specimen. Of course, one can argue that if you turn the Contessa Beach specimen upside down from the viewpoint wherein it gave the impression of the shoreline and rocky beach, the sea is atop the beach and the illusion of a landscape is lost.

The silt rich limestone called pietra paesina was formed in a marine environment during the mid Eocene epoch of the Tertiary period, approximately 50 million years BCE. The seas featured corals, fish, cephalopods and gastropods, all resembling modern groups. The land teemed with bees and other modern insects, as well as modern looking birds. Flowering plants, such as grasses, diversified, and there were new groups of mammals to eat them. Over the millennia, the rocks experienced some uplift as the Apennines rose, and this created micro-fracturing. Iron oxides and manganese hydroxide penetrated the rock, and the course of the penetration was determined by both the micro-fracturing and the spathic calcite (calcite with good cleavage) present within.

In particular, it is believed that the spathic calcite made the specific ‘designs’ possible. Blues, greys, yellowish tints and browns combine to compose ‘landscapes’. Sometimes marine fossils add to the interesting effects. These amazing rocks were discovered in the Apennines in the late 1500s and immediately became sought after, especially by the royal families and other persons of wealth in France, England, Germany and Italy. They have not been reported in any location other than in the limestones near Florence.

Some art historians believe that the presence of pietra paesina in frames and as inlays in wooden chests and cases in the palaces of the royals inspired the Baroque style of landscape paintings. Pietra paesina is expensive to purchase due to its rarity. The average small slabs of under 76mm in length are in the range of £70 to £90. The larger slabs with the most vivid images are of course much more expensive. Many of them are sold framed for an additional cost. Some dealers sell bits that were not cut as slabs as cabochons in jewellery. By contrast, Utah’s Shinarump wonderstone is considerably less expensive; twenty pounds US of rough rock (9.07kg) may cost no more than £26 to £35, which includes shipping costs to most locations.

About the author

Deborah Painter is an ecologist and general environmental scientist. She lives in the United States.

References

Kappele, William A, Warren, Gary. 2014. Rockhounding Utah: A Guide To The State’s Best Rockhounding Sites. United States: Falcon Guides. 208 pages.

Kettler, R. M., and D. B. Loope. 2019. The Origin of Shinarump Wonderstone, Hildale, Washington County. Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Paesina Stone: The Original and historical paesina stone of Florence: https://www.pietrapaesina.com/eng/

Todorović, Jelena. 2019. The Spaces That Never Were in Early Modern Art: An Exploration of Edges and Frontiers. United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 197 pages.

Utah Department of Natural Resources Home Page: http://wildlife.utah.gov/walkinaccess/authorization.php.

Trending Products