Dr G Trevor Watts (UK)

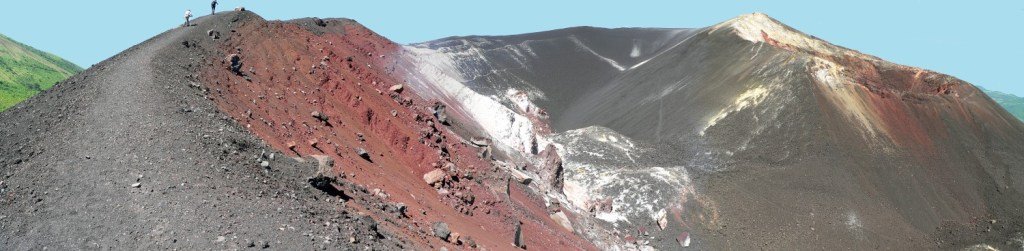

Cerro Negro (The Black Hill) is a stark, vigorous little volcano. Little recognized outdoors Nicaragua, it’s simply accessible from town of Léon and nicely well worth the effort of the hike of a couple of thousand toes up.

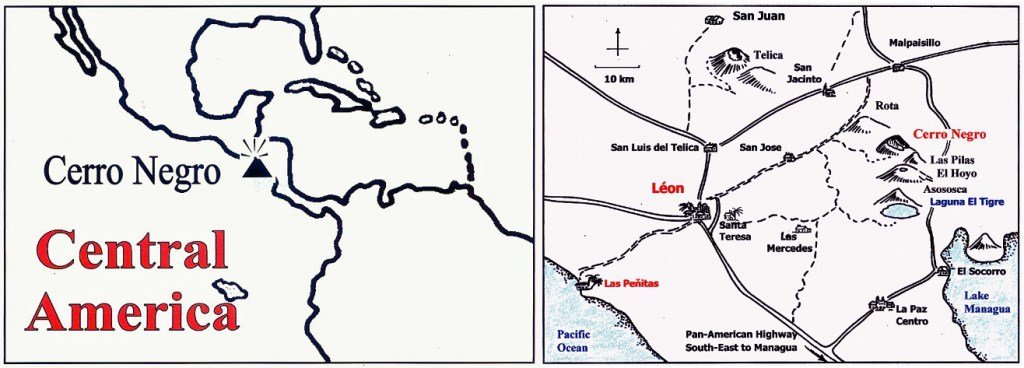

Location

Cerro Negro is about 30km east-north-east of town of Léon in northern Nicaragua. Nonetheless, it’s remoted amongst a welter of dried-out farms and unmade tracks. You may see it from miles away, however discovering it’s one other matter. By far your finest guess is to rent a neighborhood information for the day. We (my spouse, Chris, and I) went with a extremely really helpful information (see Journey information to Costa Rica, Nicaragua & Panama (Footprint Handbooks) by Peter Hutchison), Rigo Sampson, who is predicated in Léon (rsampson@ibw.com.ni).

He was accompanied by a fellow information, Flavio Parajon (fparajon2003@yahoo.es). Each information individually, however typically collectively, with Rigo’s English being particularly fluent. You get what you pay for – a neighborhood information in a neighborhood village for half a day could price US$25, however he won’t communicate English or have transport. For $100, you get transport from Léon in a four-wheel drive, meals, drinks, two guides, cell phone contact with emergency help ought to or not it’s wanted and all-day, educated consideration, along with the $3 greenback allow to enter the Cerro Negro space.

Semi-technical discuss

Cerro Negro is the latest volcano in a cluster of 4 carefully related ones alongside a fault that runs north-west to south-east. There are more than 20 volcanoes along the full length of the fault line, forming the Cordillera de Los Maribios. This is a crack that has formed where one tectonic plate is being pushed underneath another. The Cocos plate, which forms the floor of the Pacific Ocean, is being thrust beneath the Caribbean continental plate.

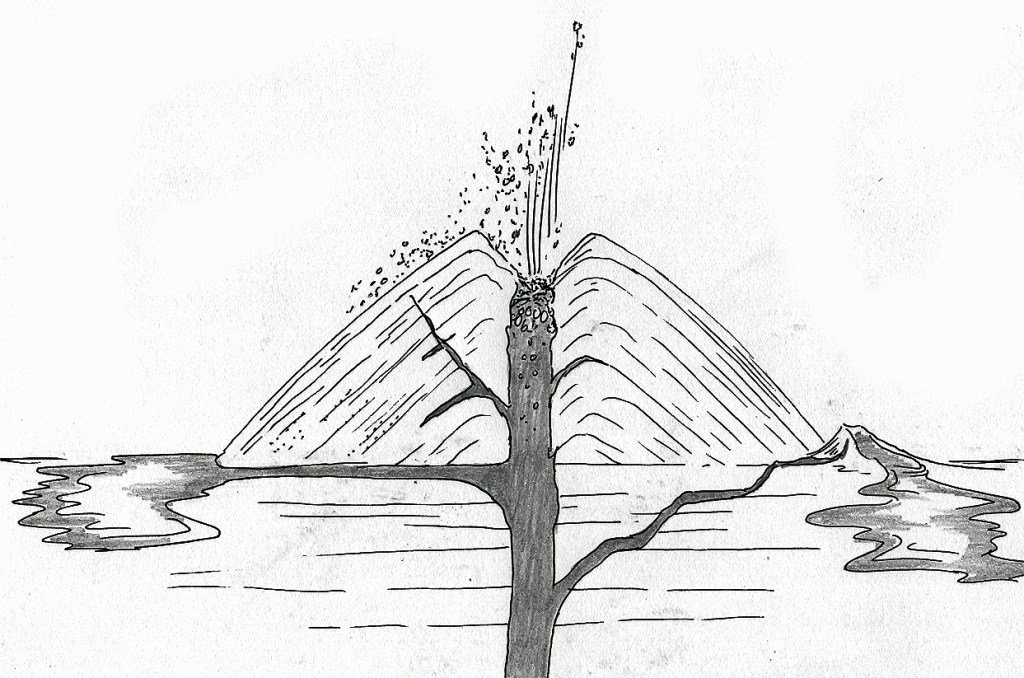

The friction of this movement produces enough heat to melt the rocks deep down in the earth, forming magma. This has a lot of water dissolved in it, averaging 6% of its mass, which was dragged down along with the sea bed, millions of years ago. This lethal mix of magma and dissolved water is pressure-forced up through the crack in the earth’s crust. Cerro Negro is a complex “composite” volcano, although it is often thought to be a simple cinder cone. However, cinder cones usually erupt for only a few months or years with violent blasts of ash and cinder, like Paricutin in Mexico.

Cerro Negro does this, but it also pours out fine-grained, dark basaltic lava and blasts out large blocks or ‘bombs’. It also produces scorching-hot avalanches or ‘pyroclastic’ flows. It has been erupting on and off for more than 150 years, far longer than a normal cinder cone. The reason for its complexity is the high water content in the magma. As the magma rises and nears the surface, its internal pressure drops and the water “fizzes out” like bubbles in lemonade when the bottle top is released. These bubbles rise through the magma. Several things can, and do, happen at Cerro Negro:

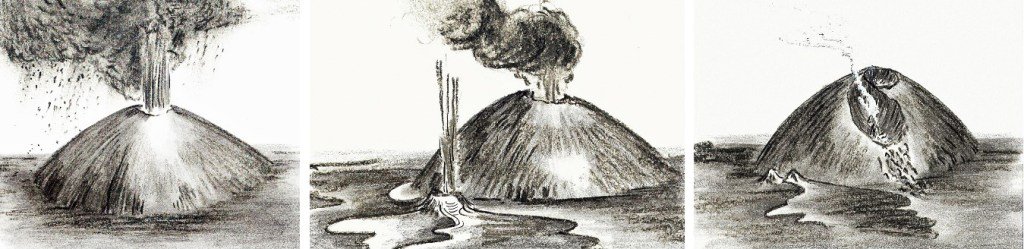

- If the magma is still hot and fluid at the surface, the bubbles will cause fairly small blasts and fire fountains, perhaps up to 100m high. These are known as Strombolian eruptions, as these are typical of the Italian volcano, Stromboli. They have frequently occurred at Cerro Negro and have been responsible for much of the build-up of the cinder slopes. Almost 80% of Cerro Negro’s output is from such relatively minor pyroclastic (cinder and ash) explosions.

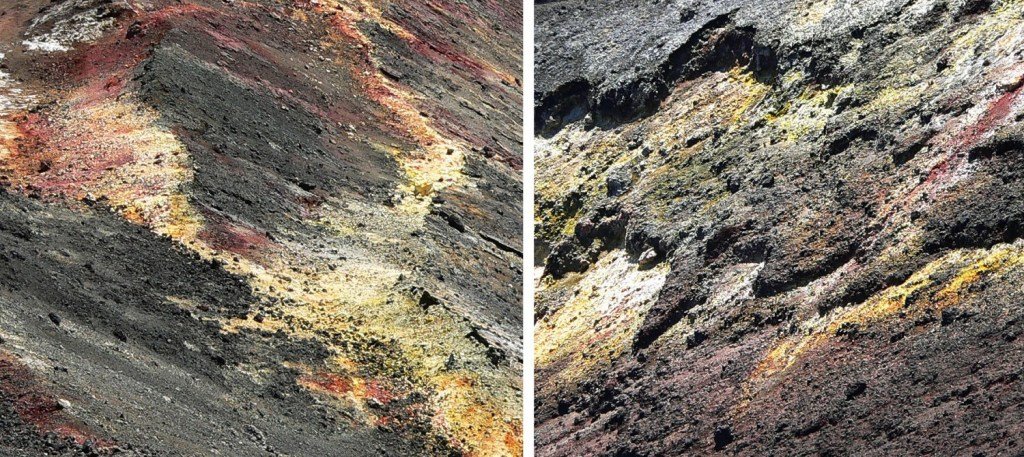

- However, the magma (or lava, as it is on the surface) may have cooled enough to solidify and form a crust at the surface. Mixed with sulphur gases and carbon dioxide, the bubbles rise as far as the crusted material. There, they may escape through cracks and vents as steaming sulphurous fumaroles (Fig. 6), adorning the rocks with beautiful and brilliant sulphur crystals and preventing the pressure from building up.

- Alternatively, the gas bubbles can accumulate beneath the crust until their pressure becomes too great and the overlying crust is blasted out in a major, violent eruption of ash, cinders and rocks. This is a Plinian or sub-Plinian eruption (named after the roman senator Pliny, who reported the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD). Ash and cinders may rise in a column more than eight kilometres high, and can spread for 30km or more downwind. As the column collapses, it can cause much larger pyroclastic flows to roar down the slopes. Rocks the size of a vehicle can be thrown hundreds of metres away.

- Whether the magma at the top of the volcano’s column becomes solid or bubble-filled, the magma lower down will still be fluid and pressing upwards. It may then find other ways of relieving its pressure by squeezing out sideways, between cinder layers and lava flows of earlier eruptions, or through new cracks that it forces open. Reaching the surface, the magma forms floods of lava from vents or small “parasite” cones with their own fire fountains at the base of the main cone.

Cerro Negro has tried them all several times and is still experimenting with different combinations of them. In general, they are called “phraetomagmatic” eruptions, meaning “steam and magma”.

Historically speaking

Cerro Negro was born in April 1850, the youngest of four brothers (with Las Pilas, El Hoyo and Rota), with lots of cousins located nearby in the Maribios chain. It began as a cinder cone, erupting large amounts of ash and cinders across the scrublands and farms, and growing to 50m high in the same year. It has grown to its present size and shape in a series of at least twenty-two eruptions. Some of them have produced very extensive lava flows, sometimes from the summit crater, but mostly from side vents and minor cones. Mostly, these are now completely buried beneath the ashy slopes of the main volcano, although there are widespread fresh-looking lava flows from eruptions in 1968 (Fig. 3) and 1995.

An eruption in 1923 produced a record amount of lava, but much is now buried under later flows and cinder falls, especially from eruptions during the late 1940s. In 1968, an eruption began in late October and produced a parasite cone at the southern base of the volcano. This very quickly built to a small crater about 20m across but, as it spurted massive amounts of lava in floods and 30m fire fountains, the crater grew to its present 100m or so diameter and is now named “Cristo Rey”. This means “Christ the King” and sometimes the name is used to refer to the main peak, rather than the small parasite cone at its foot.

This is mainly because no-one went too close when it was erupting, so they were not sure which part was doing the actual erupting anyway. Meanwhile, the summit crater erupted huge black clouds of ash and cinders that ruined crops for many miles around, and caused about 50 deaths as far away as Léon, when roofs became overloaded with ash and collapsed. The pyroclastic flows did not kill anyone, as no-one lived close by. Therefore, this was one of the rare times when a volcano was erupting very liquid lava from one vent and cindery ash from another.

During this eruption and later ones in 1971, the 1990s and 2002/2003, the summit has been raised to 721m and split into the present two craters of Las Tres Marias and Cerro Negro main crater (also confusingly referred to as Cristo Rey in some reports). The 1992 eruption produced more ash than any other eruption. The blocky, irregular lava that the trail crosses was erupted in 1995, cascading incandescently over the rim of the 1992 crater, which was enlarged to almost 400m diameter. Lava fountains rose to 300m for a time in August 1999.

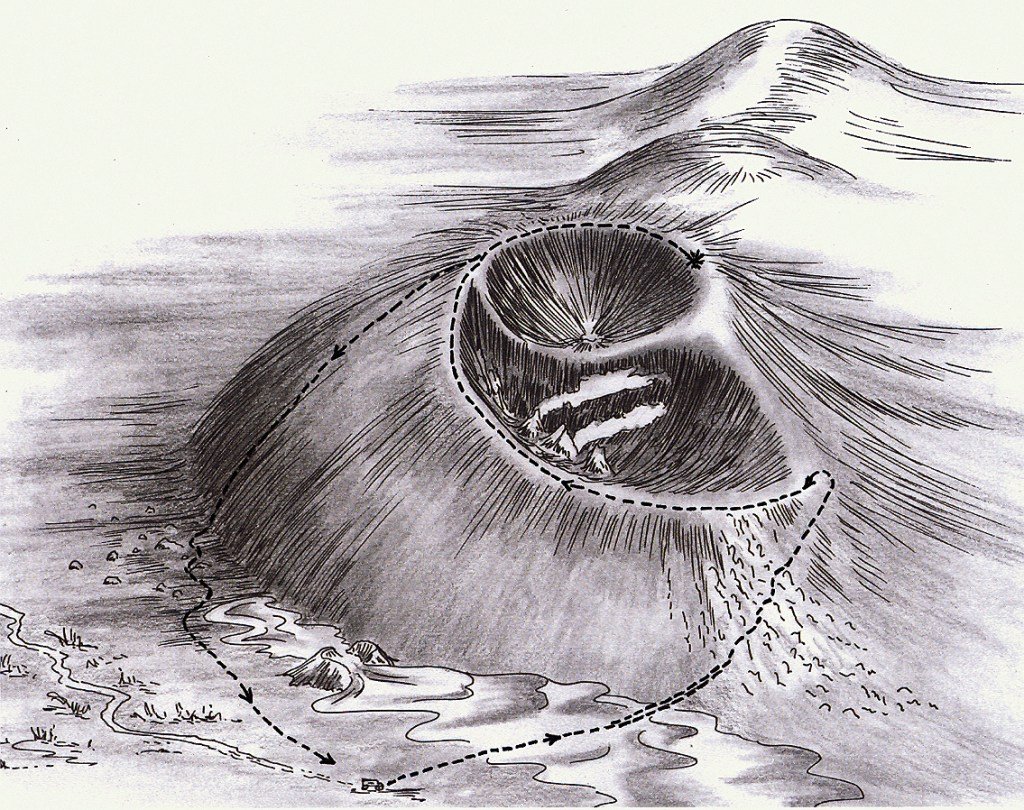

Las Tres Marias crater now has three vents continuously emitting steam and sulphurous gases with temperatures of up to 700oC. Around and among them, it is possible to see the circular pipe through which the magma rose. As the magma also flooded through cracks in the surrounding rock, it solidified into lava, forming near-vertical sheets of hard rock known as “dykes” below the surface. As the softer, surrounding rock has been eroded away, so the dykes have become more exposed as protruding walls of resistant rock.

Current Status

Cerro Negro is presently fairly quiet, although vulcanologists concluded in 2002 that there was a 95% chance of a major eruption before the end of 2006. Ominously, it hasn’t come yet, more than two years later. The eastern crater, Las Tres Marias, has very active fumaroles that emit steam, sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxide at temperatures from 45oC to 700oC. These will be releasing the internal pressure for the moment. The high summit crater is less active, but does emit some steam and other gases from minor vents. It is possible to get into both craters, but it is dangerous, not recommended and frowned on by your guide. (He certainly frowned on me!)

Getting there

It is very difficult to find the right road on your own, winding through a maze of unmade tracks in a four-wheel drive vehicle, but, of course, guides know the way.

Basically, you need to keep Cerro Negro in view and try to head towards it, whether from Léon going north along the paved road towards San Jacinto and Malpaisillo, or southwards from Malpaisillo. About eight kilometres out of Léon, turn off right (east) onto a major unmade road that looks as if it is heading towards the visible volcano. Then, take pot luck among the tracks, heading towards the rounded, black, bare mountain that is Cerro Negro.

There are good views of the nearby volcanoes, Telica and Santa Clara, to the north-west as you drive along the ashy trail through field of yucca, sesame, beans and cattle cane. This ‘road’ is, incredibly, a bus route for vehicles with names like “Return of Tyson” and “The Lightning”. They are bright yellow, 1950s US school buses. The land is very dry, with farmers having to draw water from wells of 80m depth, using their oxen to pull the buckets to the surface.

Be careful driving, not just because of the poor road surface, but also because of the ox carts carrying timber and firewood from the silent and lifeless eucalypt groves. Ramshackle farms are made of hardboard, plastic sheets, corrugated metal and planks of wood. Each is preceded by a mass of litter and is surrounded by Brahmin cattle, horses, chickens and pigs. Friendly and curious faces peer at you from the farmyards and from the playground of the tiny school. The birdlife is exceptional. We saw motmots, Nicaragua’s national bird, with its vivid turquoise plumage, as well as roadside hawks, road runners, magpie jays and vultures.

Arriving

About one and a half hours after leaving Léon, you get to where the track ends, right at the base of the mountain on a large flat area where there is a seismological station to the right of the track. To your left, there is a small parasitic cone and, in front of you, there is Cerro Negro’s black, rounded bulk. It looks ominous.

Starting from the tiny parking area at centre bottom, the trail goes across a series of lava flows around the flank of the volcano. It then rises over a boulder-strewn slope, to the lower rim of Las Tres Marias. There, it turns sharp left and follows the rim of both craters to the highest point. The return is straight down the cinder slope, then across the boulder field at the bottom. It is possible to skirt all the way round the small crater of Cristo Rey or to enter it, if you still have the energy. There, you can see how the upwelling lava divided, with the flow travelling in opposite directions at different times.

Make sure you have plenty of water, then head towards the right side of the volcano on foot or mountain bike, where there is a very clear trail made by volunteers for occasional sporting events. This trail quickly fades away as it rises gradually through loose cinders and ash, before coming to a patch of blocky rubble lava after less than one kilometre.

Here, it is necessary to scramble upwards across loose scree, looking for where the trail re-appears ahead of you. Soon, you are curving left around the flank as the trail rises. It is hot, but a strong breeze is almost always present and welcome. Suddenly, you reach the rim of the crater at a low shoulder. To your right, you can look into a recent crater with its three smoking fumaroles, ‘Las Tres Marias’ (The Three Marys). Further over, there is a glimpse of the main crater above you.

The trail continues upwards along the rim of the crater, following a gentle slope. To the left, there are superb views across the lava and ash plains, and down into the parasite cone of Cristo Rey with its stark lava flows, near to where you parked the vehicle. The walking is very easy. However, the warmth and wind mean that you really do need your water flask at the ready.

Further to the left, stretching into the northern distance, you have glorious views along the Maribios chain of volcanoes. Actually, our trip took place on the day we should have been climbing Telica, but it had erupted the previous day and overnight, so it was thought safest to postpone our visit for a couple of days, in favour of this one to Cerro Negro.

To the right, there are superb views into the 350m-wide crater of Las Tres Marias. As you progress along the gently rising trail, you get better and better views of the main crater beyond Las Tres Marias, and eventually arrive at the highest point, looking down into the inverted cone of the crater.

The view from the high point of the rim is one to linger over. It is a picnic spot you will never forget – the main crater to one side and awesome views along the smoking Maribios chain on the other. Our guides had prepared, and carried, a feast of local meats and cheeses with crusty bread, fresh fruit and fruity chocolate bars.

There are thousands of large flying insects there on the rim, seeming to hover on the warm updraft wind. They didn’t bother us, but apparently they can sting. Sometimes, anteaters go up there, searching for these insects.

Look to the north, along a hill that stretches away from Cerro Negro. This is the extinct volcano, La Mula (The Mule). To me, its four-humped ridge is more suggestive of a couple of camels than a mule. This is a possible way down (and up), but it is a very long drag from the nearest track. There is another, very long route to the east, across open scrubland. People sometimes use this faint trail as part of a long-distance trek that takes in a series of the Maribios volcanoes in a few days, camping overnight between each.

Eventually, rested, fed and watered, you have to descend. The way down is another highlight of the day. You drop straight over the edge to the south, directly down the ash slope, almost a 1,000 feet at an angle approaching 45o, although it feels much steeper, as it is totally exposed and bare.

A few years ago, a French cyclist managed to descend this slope at 172kph. He was in hospital for two months after his crash and the bicycle never recovered. It was the sudden break of slope at the bottom that did it, where there is also a scattering of large lava bombs. At that speed, you just can’t steer round them. If you “scree-run” in the style of an ice skater or cross-country skier, it can take five minutes. However, some patches are very solid and are treacherous to runners’ knees, ankles and other easily broken bits. You could also try sandboarding if you have a death wish (some do).

Once you reach the base, it is a 15-minute walk on the flat back to your vehicle. You cross an ash and boulder field, and also the lava flows, including the one from the 1968 eruption of Cristo Rey. If you have time, this small parasitic crater is a fascinating place to explore, with two outlets for its lava.

| Other volcanic highlights |

|---|

| A highly recommended diversion while returning to Léon is the gorgeous crater lake, Laguna El Tigre (Fig. 21). Along the route, there are superb views of other nearby volcanoes – El Hoyo (Fig. 19), Las Pilas and Momotombo (Fig. 20). The name given to the lake by the indigenous people is Tecuanchianmitl – “surrounded by jaguars” – but vulcanologists refer to it as the Asososca maar. A maar is a wide crater with relatively low rim walls. Very few people go there because it is remote, difficult to find and is privately owned. Some guides know the way and the land-owner. Get the right guide and you can swim in the glass-clear lake, dry off in the hot afternoon sun, and then rest in a hammock with a cold drink in the shade of a rough lake-side shelter. It is a wonderful place to spend a relaxing couple of hours. |

| Alternatives for the unconverted |

|---|

| Léon is a dilapidated former colonial city with a history written in violence until quite recently. There are many attractions related to art, literature, architecture, religion and history. The hotel ‘El Convento’ is an atmospheric place, full of character, to stay, reputedly with the best restaurant in Léon (Fig. 22). It was certainly excellent in terms of flavours, tranquil courtyard and value for money. There are other hotels and hostels for the budget-minded, including a very pleasant and homely one owned by our guide, Rigo Sampson. |

Further information

I am not aware of any books about the minor volcanoes of Central and South America, but the Internet has information about them. You might try:

Trending Products