Dr Trevor Watts

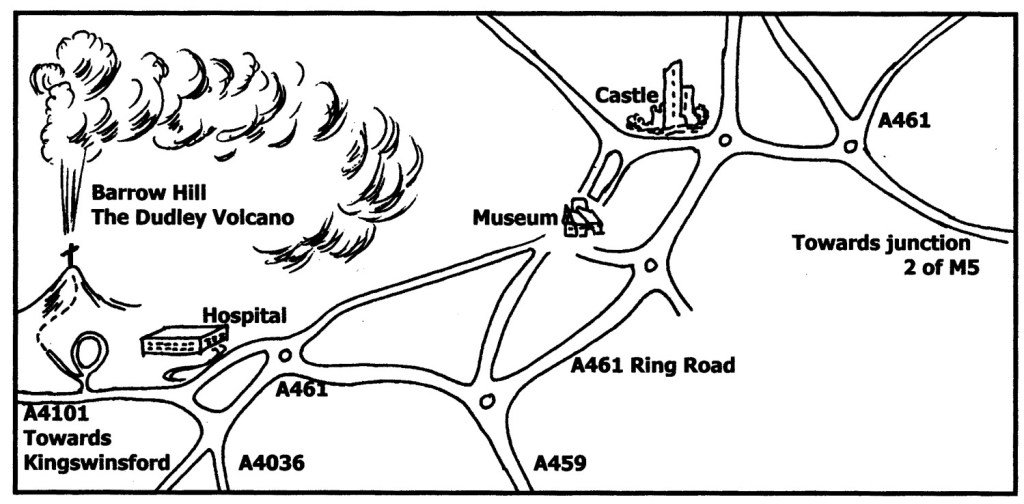

Barrow Hill (Fig. 1) is slightly gem. It’s just about unknown, very accessible and in the course of a big city – Dudley, within the West Midlands of England. These days, it’s virtually swallowed up within the western suburbs of Birmingham (Fig. 2).

A short abstract of the geology

The hill is the stays of an historical volcano that was lively 300 million years in the past, in Carboniferous occasions. It’s probably that there was one principal cone, with a summit crater, and not less than one smaller parasite cone on its flanks. Faults (Fig. 3) have shattered the earth on all sides, making the geology very sophisticated, particularly for the coal miners who have worked the seams beneath the magma chamber.

In its Late Carboniferous heyday, Barrow Hill was high and very active. It was one of a complex of volcanoes in the area, which are still evidenced by other eroded hills in the neighbourhood. The region was one of vast tropical deltas and swamps, filled with steaming lagoons, giant dragonflies and sweltering temperatures. Therefore, today’s coal seams were laid down with marl and clay layers among them, reflecting periodic inundations by the sea and fluctuations of water level.

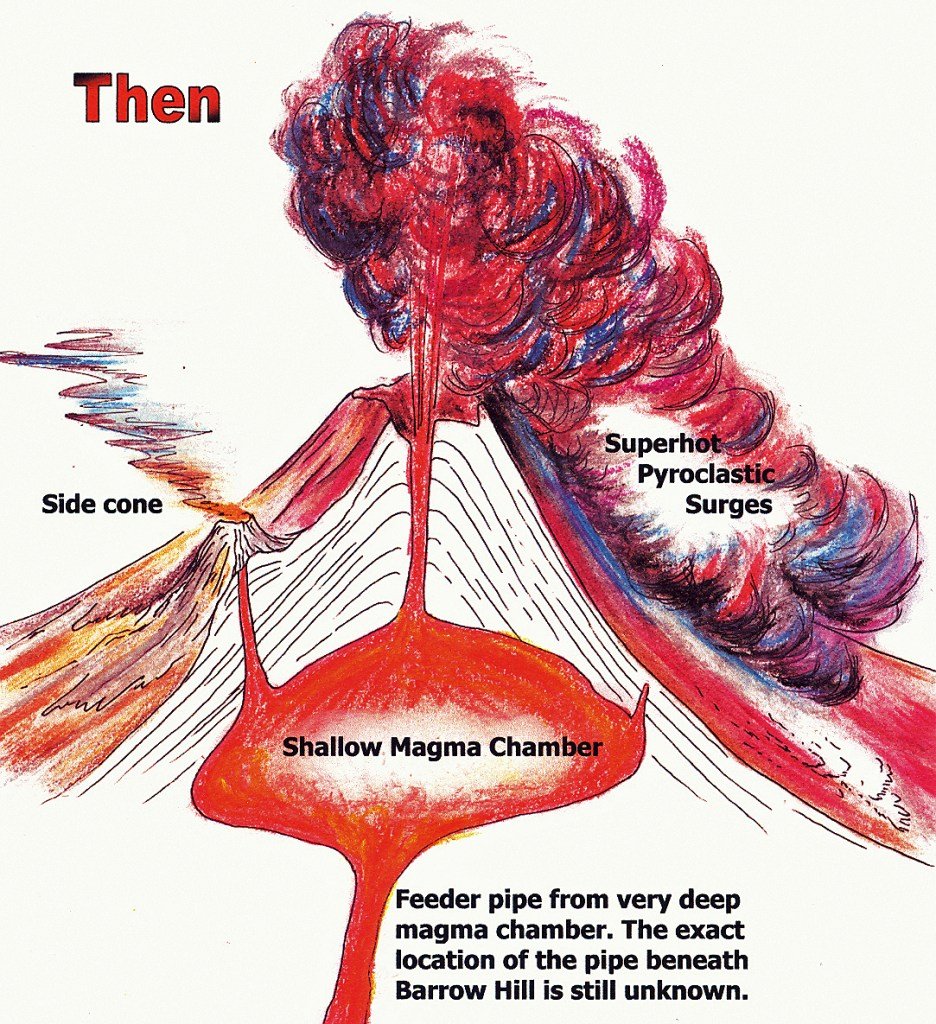

However, the land was slowly rising and drying out, giving rise to coniferous woodlands. Into this landscape, magma rose from a great depth through a vertical pipe that has not been precisely located, despite the maze of mine shafts and tunnels beneath the chamber. This molten rock pooled up before it reached the surface and then fed upwards again to the actual eruption spot. The volcano exploded with violent, Plinian-style explosions of pyroclastic blasts and dense ash clouds (Fig. 4), spreading lava and ash for miles around, and sending super-heated surges of gases, ash and lava fragments down the flanks.

One of the thicker ash deposits is world-famed for its fossils. Over an extended period, pyroclastic clouds (Fig. 5) and ash-rain, from the main crater and side vents, produced large amounts of hot ash and fine debris. It was enough to engulf a forest of small coniferous trees, but was not quite hot enough to completely burn them.

However, they were scorched and their remains still stand, entombed in the lowest layers of the ash, still showing the charring on the bark. They are the oldest known 3D (standing) tree fossils in the world. Probably wisely, they have been re-covered by conservationists to prevent their collection.

The history of Barrow Hill

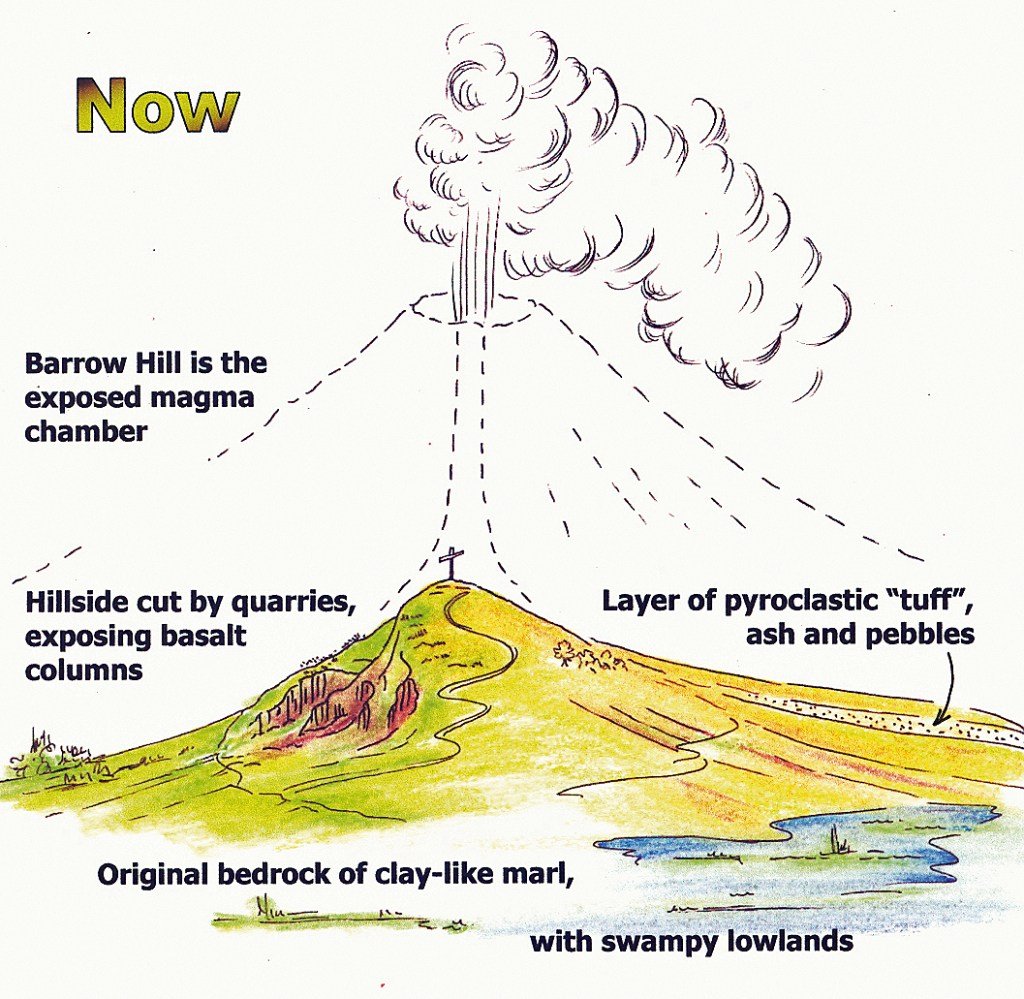

Nothing volcanic has happened for about 300 million years. However, erosion has continued apace and, for a brief period, so has mining and quarrying. Almost all of the volcano itself has been eroded away by the elements. The present Barrow Hill is the volcano’s foundation, probably an upper remnant of the magma chamber, although there are layers of ash and agglomerate (that is, mixed sizes of volcanic pebbles) on the north and northwest slopes.

In the nineteenth century, parts of the volcano’s sides were removed by the quarrying of basalt for road-building. This rock is an especially hard type known as dolerite. Beneath the basalt outcrop, the country rock is Carboniferous Coal Measures and it was extensively mined for many years (Fig. 6).

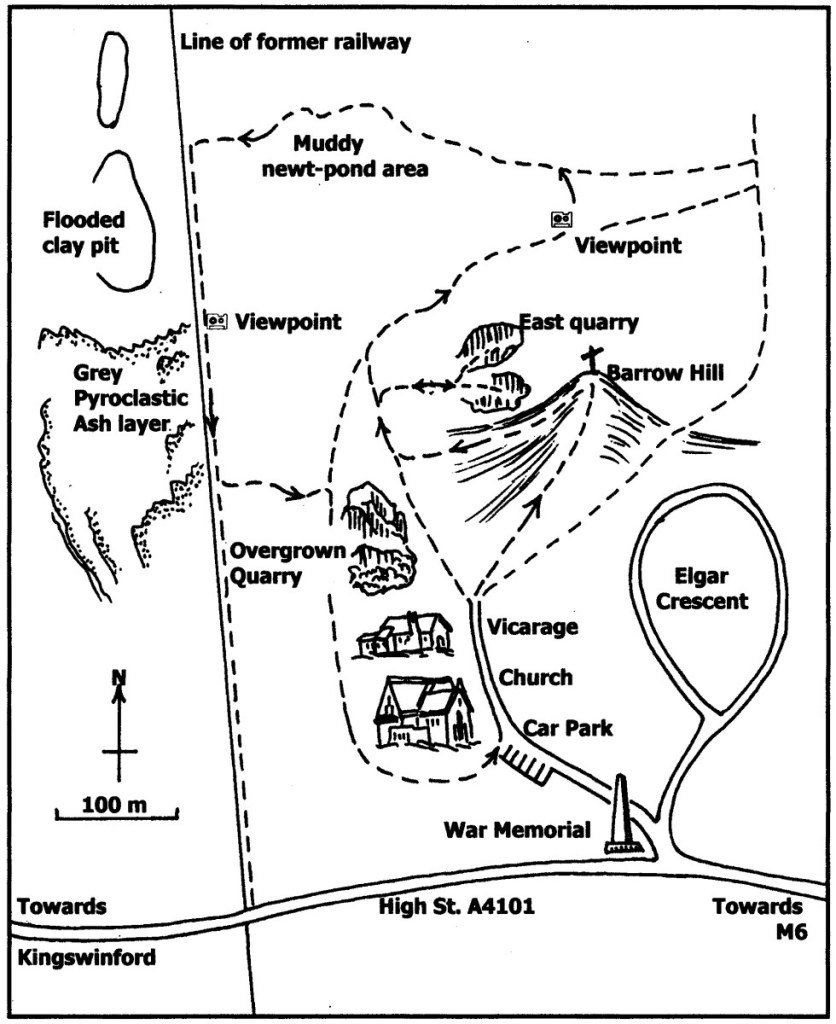

Not to be outdone, clay miners also had their share, by removing huge quantities of the swamp-formed clay (or marl) for brick-making. However, nowadays, Barrow Hill Park (Fig. 7) is a beautiful site for summer picnic-makers, evening trail bikers and naturalists.

Current Status

Dead… Technically, extinct! There is little risk these days, unless you try to explore the most overgrown quarry, where it is very uneven underfoot, or are hit by reckless trail bikers.

A tour of the volcano

Once you’ve parked next to the church, walk up the lane, past the vicarage, for about 100m. Go through the gate and take the middle of three footpaths, directly up the hill, a little to the right. And there is Barrow Hill before you. The hill is quite imposing, but not very high, at only 152m above sea level (and less than that above the surrounding countryside). It is a pleasant, five-minute walk to the top, giving good views of the area.

Look at what you are standing on and you will see the dark dolerite bedrock. It proudly supports the huge cross on the summit, clad in its galvanised metal sheath. When I stand here, my mind drifts back to time of the active volcano. I imagine the molten rock coursing all around me, rising violently up to the surface, bursting out in a crater hundred of metres above my head. I am always awed at the thought that this is the very spot where it happened all those millions of years ago.

For a few moments, enjoy the view across the plains to the distant Rowley Hills, the hospital grounds, Dudley stretching away to the far horizon (Fig. 9).

From the cross, take the track to the west, along the short crest, then down the hill and turn right onto the main trail. After less than a 100m, you turn right and make your way into the east quarry (Fig. 10).

This has three faces. One has tall columns of basalt about 30cm across (Fig. 11). Here, the magma cooled fairly slowly and shrank a little.

This slow cooling and shrinkage allowed it to form elongated ‘columnar crystal’ shapes, although they are not really crystals. They are mainly hexagonal in cross-section, although this cannot easily be seen, because of the soil and undergrowth covering the rim of the quarry. They are not as good as the ones at Fingal’s Cave in the Hebrides, but this is Dudley we’re talking about, not Staffa, the Giant’s Causeway or Devil’s Tower.

Another quarry face shows the junction where the molten magma came into contact with the local Etruria Marl. In one exposure, there is even a mass of reddish marl that broke off and was completely surrounded by the subterranean magma. This marl (or clay) is often red or purplish and it forms beds of material that was weathered from earlier basalt formations, taking on its hues through the action of oxygen on its iron content. In other places, there are fragments of partly decomposed basalt still to be seen.

As well as being baked by the later volcanic intrusions, the marl often suffered cracks of great length. Later again, superheated liquids rose through these cracks, impregnated with different minerals from below. Within these ‘hydrothermal vents’, the minerals began to line the walls of the cracks, as the liquid cooled, eventually filling them completely. They are seen today as lines of pale calcite in the south face of the quarry.

Around the quarry floor, you can easily find pieces of near-black, sharp-edged basalt that was formed deep in the base of the volcano. Mixed among them are pieces of reddish lava, rough, lumpy and sometimes bubble-filled – further proof that this really was once a volcano.

Leaving the quarry by the same route you entered, follow the track northwards. If the day is fine, you can enjoy the view over the low-lying fields and wild-flower meadows, and look back at the steep, wooded north face of Barrow Hill (Fig. 12) before wending your way around the recently re-created newt ponds to the line of the old railway. About 200m down the track, there is a spot where you can see across the clay pit area.

Most of the time, it is part-flooded and is also private land, though much used by local people. Across the low-lying land, you can see an embankment with a thick layer of grey rock. This is the ash layer that engulfed the coniferous forest, slowly and gently at first, then in violent pyroclastic eruptions, leaving ash, tuff, breccia and agglomerate behind, mixed together or in layers (Fig. 13). You are not allowed to go into the clay pit area, but lots of people do – there are footpaths across it and locals use it as a shortcut to and from a nearby housing estate.

A little further down the rail track, take a side-trail to the left. This leads to the western quarry. It has not been cleared and is deeply overgrown with brambles. The quarry floor is extremely rough and the rocks are quite unstable. Although better than in the east quarry, the exposures are not easily seen and it is not recommended that you visit there, not without very sturdy footwear and a good first-aid kit, anyway.

By-passing the quarry, you skirt around the churchyard, where there is a very interesting variety of gravestone materials, many made from local rock. Some of the more ancient ones are built like nineteenth century fireplaces or hearths – glazed fire-brick edifices made from locally mined and fired bricks, including those made from the Etruria marls. And then back to the car park.

All told, it takes perhaps two hours, unless it’s a sunny day and you’ve brought a picnic…

| Location |

|---|

| Barrow Hill is in a conservation park just off the A4101. This is the High Street, between Dudley city centre and Kingswinford. It overlooks Russells Hall Hospital. Coming from Dudley, leave the Ring Road A461, onto the A4101. Pass the hospital, turn right next to the war memorial and then immediately left into Vicarage Lane. After about 100m, there is small car park just before the church on the left. This gets crowded in summer, but if you arrive early, you’ll be fine. Or there is a bus service from the middle of Dudley. If you want to stay locally, there are plenty of hotels and guest houses nearby. You could try the Kingfisher Hotel at Kingswinford (Tel: 01384 273763) or The Bush Inn at Dixon’s Green, Dudley (Tel: 01384 253753). Both are within about a mile of Barrow Hill. |

| Other volcanic highlights in the region |

|---|

| Call at the Dudley Museum & Art Gallery in town first. It’s free, and good on local geology and fossils, including some very informative leaflets about Barrow Hill. Opening times are 09.00 to 17.50 every day. To the southeast of Dudley, into West Bromwich, there are the Rowley Hills. This is another, more extensive, region of volcanic dolerite rocks. However, they lack the clear exposures of columnar formations seen at Barrow Hill.Further afield, there are volcanic remains of a similar age in the beautiful Lathkill Dale, on the southern fringes of the Derbyshire Peak District. And there are more between Matlock and Bonsall, also in Derbyshire. |

| Making a full day of it |

|---|

| Around Barrow Hill Park, there are nineteenth and twentieth century industrial remains of a colliery and brickworks. There is also a wealth of wildlife. Great crested newts are common here, as well as tortoiseshell and other butterflies. The area is rich with rare meadow flowers. Dudley Museum & Art Gallery has all the information and leaflets.Wonderful modern, mainly-metallic sculptures are scattered throughout Dudley in celebration of the Year 2000 Millennium, especially along the ring road, the A461. The eleventh century, Dudley Castle (Fig. 14), is located in the centre of town. There is the West Midland Safari Park the grounds, open daily at 10.00am until late afternoon, with charges for parking and entry. For more information, try: http://www.dudleyzoo.org.uk.htm. It is only about 20 miles down the A449 to the West Midlands Safari Park at Bewdley. Variable opening times, usually 10.00am daily. |

Trending Products